(Interview by Roberto de Jesús Quiñones Haces with Guantanamera writer Rebeca Ulloa Sarmiento)

I remember that one Sunday in the 1980s, I met Rebeca Ulloa (Guantánamo, February 7, 1949). It was at the home of Dr. Florentina Boti in Guantánamo, an essential place for the history of the province’s culture and even the nation, because the first great Cuban poet of the 20th century, Regino E. Boti, was born there. His influence among Cuban intellectuals in the first half of that century is convincingly demonstrated in his abundant correspondence.

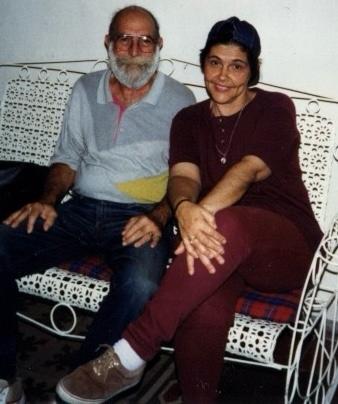

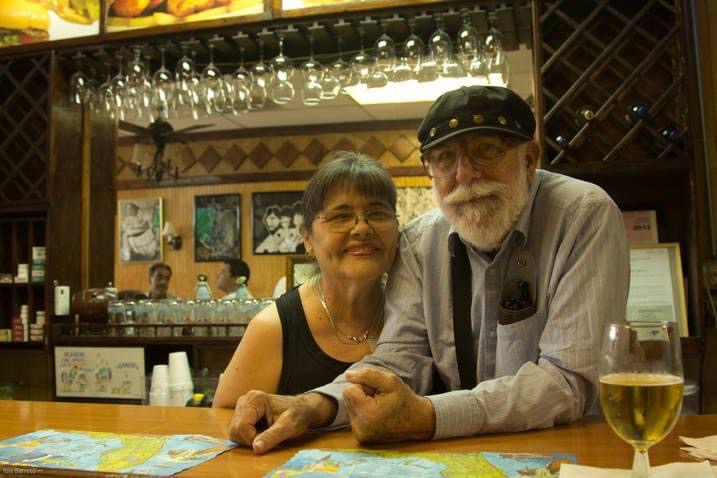

Rebeca was the first president of the UNEAC provincial committee in Guantánamo in 1987, a natural leader for the territory’s writers and artists. In 1992, she moved to Havana and joined her life with Arístides Pumariega, one of Cuba’s leading cartoonists. She later lived in Colombia and then settled in Miami, where I saw her again more than thirty years later.

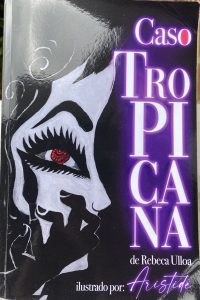

The publication of her novel “Caso Tropicana” (Digital Media 305 in collaboration with Arte Mundo Latino, 2023, special edition for Amazon) sparked my curiosity, so I bought and read it. It is a work that merits recreating an environment rarely addressed in Cuban literature. Her reflections on the political situation in Cuba in the 1960s and several of her characters, stripped of the stereotypes common in much contemporary Cuban literature, were unique to me. Additionally, her skill in narrating a captivating story drew me in from the first chapter.

From that reading and various memories, the idea for this interview emerged, partially published by Cubanet on Monday, May 13, 2024. Due to its length, I only sent the responses to my first three questions about the novel to the dean of Cuban independent press. Now I share the full interview on my blog.

How did the idea of writing the novel “Caso Tropicana” come about?

It’s a long story that began about 30 years ago when I started living in Havana. In Guantánamo, as a writer for the CMKC radio station, I listened attentively to Radio Progreso’s dramatic block and noticed how those radio novels were told, using effects, dialogues, and music. Later, in my scripts for local radio, I included some dramatized segments.

In Havana, I began writing children’s series, stories, and dramatic works for Radio Arte, which distributed the recordings nationwide. I also worked at Radio Progreso, where I did radio versions of novels like Isabel Allende’s “Eva Luna” and Marcela Serrano’s “Nosotras, que nos queremos tanto.” The version of “Eva Luna” won the Caracol award from UNEAC in 1997.

It was Erick Kaupp who suggested I write crime novels, and one of them was the first version of “Caso Tropicana.” It had 50 episodes that were recorded and edited. I didn’t use a narrator; the scripts were pure dialogue. To my surprise, it became popular in UNEAC and UPEC, and some friends attended the recordings. In one episode, there was a parade in a “Ball.” Thinking it wouldn’t be censored, I set the story in New York. For the parade, Arístides designed the dresses for the Drag Queens. Writing the scripts and attending the recordings was very fun. The director was Norma Abad, and the advisor was Orieta Cordeiro. I was in the big leagues of Cuban radio! But my joy was short-lived. The novel was censored and never aired. Despite placing it in New York, they erased it. We fought, requested meetings with the national Radio management, which dictated the sentence: “Very good but not in our content.”

I started to consider setting the story in Cuba. Living in Colombia, I began to work on the idea seriously. No drugs, no New York, the plot would be in Cuba, the crime case would involve the so-called revolution and counter-revolution, and the setting would be the nocturnal Havana of the 50s and 60s, which has always attracted me. Having Arístides, a witness-protagonist of that Havana I didn’t live, next to me offered a golden opportunity, so I set the ambitious project in motion. That’s how the literary project began.

Havana had a very intense nightlife during the republican era, especially in the 1940s and 50s, which is present in your novel. Did you research this? Are the characters based on real references or entirely fictional?

I had to research a lot, but Arístides was my most valuable source. He had been a musician in the 50s and participated in the opening of places like “La zorra y el cuervo,” “La red,” the tea dances at the Copacabana hotel, and worked in many others, besides knowing the Tropicana cabaret very well: that’s priceless! Arístides’ cousin married a nephew of one of the Tropicana owners and also gave me a lot of information. I watched videos about the cabaret, reviewed magazines from the time, confronted data, all of which helped me create the novel’s atmosphere. Many characters are based on real people. I had invented the character of Sofia as a Cuban security infiltrator dancer, and in my research, I discovered there was someone like that in 1959. Arístides also told me about the “Rumba Palace,” another important site in the novel. Living in Colombia gave me easy internet access, intensifying my search and allowing me to incorporate other characters into the plot. As for the references to changüí and Marcano’s family environment—the novel’s main character—it’s clear that it stems from my Guantanamera roots.

In Miami, I talked to Cubans who opposed the dictatorship. That information allowed me to depict what appears in the novel as “the Movement,” my homage to the organization “La rosa blanca.”

Your novel initially puzzled me because I couldn’t identify whose narrative viewpoint it was. Then I concluded there were different viewpoints. It still seems like an atypical novel. How did you conceive the writing process? How did you manage to captivate your readers?

It also seems like an atypical novel to me; it’s more like a film script. I conceived it with a hidden, surprising ending, and I think I achieved it. I liked the idea that each character had their protagonist space, that their previous life was told and inserted into the plot. I had a lot of fun with the character of Hernán Fuentes because of his hatred for Marcano, his ambition to possess Nina. Both this character and Mazagüero are disposable; they earn the reader’s hatred but make the plot entertaining. The same goes for a “positive” character, Captain Marlon of Cuban security.

There’s an omniscient narrator who knows everything and gets involved in everything, even making random comments like, “as my friend Helio Orovio says.” He describes a place in third person, then takes on a second-person perspective, speaking to the character. Yes, I believe there’s a first, second, and third person narrating the novel, not for show, but because that’s what the creative act demanded. The viewpoint is malleable, like a voice adjusting as required by the plot. I didn’t seek it; it wasn’t my intention or a contrived literary structure. I can’t do linear narrative, a serious narrator. I’m very informal, and I dislike walking on well-trodden paths. Whether the novel is atypical or not, I’ll leave that judgment to the critics.

You were the first president of the UNEAC provincial committee in Guantánamo in 1987, a significant year for culture in that province, the poorest and most remote in the country. I know you were never a “docile salaried official thinker,” but I think holding such a position must have caused several disappointments and mixed feelings between the Rebeca I know and the official mandates. Was that so? Why did you accept that position?

The most surprised on election day was me. I was elected with almost all the votes of the first UNEAC delegation in the province, as you said, the poorest and most remote in the country, but that was after the 1959 tsunami when Castro arrived with his gang, wrecking everything. Until then, Guantánamo was a wealthy municipality. It had the Caimanera salt flats, about seven or eight sugar mills, paper mills, coffee plantations, and the American naval base in the bay. And what can I tell you about social and cultural life? Private and public schools; there were about eight or nine cinemas and numerous cafes, clubs, and bars. In short, the provincial aristocracy, as Professor Mercedes Cros Sandoval calls it. Guantánamo enjoyed good artistic, cultural, and social health, evidenced by the friend Lemus, who has published the Guantanamera archives of writers and is now researching visual artists and journalists. And there are many.

Returning to your question, I was the second secretary of the organizing committee but wasn’t the official choice to lead UNEAC because I wasn’t a member and never was of the UJC or PCC. It’s curious because, at that time, all the provincial presidents were members, except Ariel James from Santiago de Cuba and me from Guantánamo. In university, they processed me for the Communist Youth three times, but I wasn’t approved. I was a leader of the FEU at the School of Letters of the then Faculty of Humanities at the University of Oriente, holding several positions until I became president. Later, I was secretary of the union section at the Education center where I worked in Santiago de Cuba before starting in television. Well, those were the positions I held. All were positions I held through democratic elections, never by the party’s express designation.

The day before the election to form the UNEAC provincial committee in Guantánamo, the party met with the militants of the new group forming that first committee in 1987. You would join later because you came from the UNEAC in Cienfuegos, right? I imagine the orientation was to propose each other, as happened in the meeting. When I was proposed, I was in the penultimate place on the ballot, and the last was Enrique Lomba. In the voting, I won for president, and Lomba as vice. Imagine, the militants must have given me their votes, as well as to Lomba.

Why did I accept? What can I tell you? At that moment, we were a group with a lot of desire to do things, which we did. I think I still suffered from some “revolutionary romanticism” that encouraged me to try to do what I thought. There were many things we proposed, and the agencies and institutions that should have done them didn’t.

I came from a frenetic activity at the university, where I had been president of the FEU at the School of Letters and editor-in-chief of its Literary Workshop magazine and the Mambí magazine. Then I worked in the television of Oriente.

I confess I was back in the village and felt like I was suffocating. I had no identity with the city, and it was Regino Eladio Boti who, with his mountain, sea, and the smell of salt in his verses and watercolors, gave me identity, as Lemus says, “Guantanameritud.”

I think we did many important events in those first years, locally and nationally, exhibitions of visual artists, we repaired the headquarters, better, we accommodated it. I took the position seriously, as I do with everything because that’s how I am. That first group of UNEAC members in Guantánamo was diverse, complex, but we managed to work together, be friends, or at least I felt that way. It wasn’t an easy time, but I was happy because I didn’t have to account to anyone in the province, or at least I didn’t. Of course, they tried to bend me, but they didn’t succeed. UNEAC’s statutes stated it was an autonomous organization, and I clung to that.

I remember the Party wanted to send me the cleaning staff and the administrator they chose, and I flatly refused. I must say that on this point and many others, I had the support of the national UNEAC. I can’t say otherwise. When repudiation acts were held against some artists, I think they were actors, they called me to a meeting with the Party demanding that we as UNEAC should participate. I said no, that we wouldn’t participate. When I called the presidency in Havana, they told me I had done well.

Disappointments, confrontations, discussions, disenchantments, and disappointments were there, but I also enjoyed many achievements we reached, or at least for me at that time they were. Such was the Boleros de Oro Festival, radio and television meetings, literary criticism, visual artists, and musicians. We supported events that weren’t UNEAC’s but were important for the province. Around UNEAC, there was a group of people concerned with “doing,” even if they weren’t committee members. We didn’t question anyone. Neither by religion nor sexual orientation. Everyone was welcome in our headquarters. Very important, I believe, was the creation of the “Guamo” award, which we did by nomination, and then a jury made the decision.

When the first end of the year arrived, I thought it was important to have a celebration with artists and their partners at the headquarters. When I asked the Party member who attended us at that time for four boxes of beer, he said if he gave them to me, four families would go without that quota. I, still somewhat naive, even felt bad for making the request. The next day I went to the factory with some bottles to see if I could get syrup to make refreshments and see how we could invent something. It almost seems like a joke because when I was waiting for authorization to enter, a truck loaded with beers came out, and as it had to stop at the control point, I saw that it was the same “comrade” who had given me the lecture the day before. I approached and asked how many families would go without the beer quota. Of course, he authorized me, and we could have our party. This is just an example. I don’t know how, but we managed to gain respect and received a lot of help from Culture and Popular Power.

I often faced dispositions, orientations, and especially had several confrontations with… how do you say, “the comrade who attended us” for state security. To cite some examples I remember, in a national literary criticism meeting we convened in the province, Ángel Carpio spoke in his presentation about Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s work. You know, the next day he appeared, and I had a strong confrontation. What’s curious is that “the comrade” wasn’t at the event. Ah, with your poetry book, “La fuga del ciervo,” it was a tragedy. I imagine I told you about it. He said the deer referred to Castro. I had to rebuke him and accuse him that he was the one saying it because you didn’t, and none of us saw it that way. Everything said in UNEAC was subjected to analysis, I imagine, because every day he came with something. One day, to see if he left me alone, I said our group followed Martian ideology and aesthetically followed Boti.

I think the most intense clash I had was with the first visual arts salon we did. The night before the inauguration, when it was already set up and the next day guests from Havana and the national presidency arrived, the Party’s culture bureau character appeared and started saying we had to remove two or three paintings because, according to him, they had problems. The discussion was strong, but we stood firm, and I said I would take responsibility for what happened. The next day, the jury worked, and no one said anything about the works the character had tried to remove. He stayed quiet.

Another serious problem I had to face was that, especially in the Literature section, at the beginning, I think the only heterosexual was me. And the harassment was terrible. I didn’t say anything to the artists because I didn’t want them to feel bad. Also, because we admitted to the committee—with Havana’s approval—Father Valentín from Baracoa, an excellent photographer. In short, we were then a very atypical committee.

There would be a long list of situations like the ones I just told you. But I must be honest and say that I managed to receive help, materially speaking. Since I had no driver position or car budget but had a Soviet jeep sent from Havana, the provincial Culture directorate provided me with a driver, and we solved fuel vouchers without having an allocation. It was very funny because I had a budget for the headquarters, but we still didn’t have it. They told me I couldn’t take money from the headquarters budget for the car, but I needed it, so I did, and of course, those were discussions and arguments, but we always came out fine. I remember even the furniture factory gave us a living room set, dining room set, and others for the inauguration, and I had to argue a lot with the national directorate to get the money. There are thousands of anecdotes, and efforts to move forward as well. I remember what we had to do to get a grand piano for the concert hall, the tiles, the floor, the marble to cover part of the walls of the hall, and the tiles for the roof. For those who don’t know Cuba, it means nothing, but we know how to get something that elsewhere is easily obtained or insignificant; in Cuba, it becomes a calvary.

Many artists and writers lamented your move to Havana in the mid-90s. After that, UNEAC in Guantánamo was chaired by Jorge Núñez Motes, and since then, the open exchange of opinions among the membership was limited to the extreme, and election fraud for that position reached scandalous proportions. Today, that individual is regarded in Guantánamo as an appendage of the Communist Party, of which he is a member. Is it true that you recommended him for the position? Have you kept track of what this man has done against several writers and artists in the province?

1992, exactly. My four-year term ended, and I didn’t want to continue in the position; I didn’t feel comfortable anymore. They say God’s timing is perfect, and it seems true because it coincided with my relationship with Arístides.

It was extremely difficult for me, if not impossible, to return to work at the radio station or the culture directorate after holding the position. It was as if the destiny was marked. The decision was to leave the village. I confess I did it with much pain. Indeed, I was the one who proposed Jorge for my replacement. Jorge and I had a long history of many projects and friendship. I might not agree with him, but affection isn’t something you give and take mechanically. We had worked very closely in managing the committee. It wasn’t easy for them to accept my proposal, but he eventually led the provincial committee. At that time, I thought it was the best choice.

It’s not the first time I’ve heard things weren’t the same after I left. I was surprised to learn he was a Party member. I imagine he found no other option if he wanted to continue in the position. They practically harassed me to submit my Party application, as I was no longer of age for the UJC. And it took a lot of effort to repeatedly delay the matter because, by then, I wasn’t interested. I suppose I was like a stray sheep they couldn’t control.

I haven’t had direct or complete information about UNEAC’s course in Guantánamo after I left Cuba. Even in Havana, I maintained my connection with the province. I’ve received some references, like in your case, when they turned their backs on you and other common friends; but I haven’t had a conversation with him about it.

When and where did you definitively break with UNEAC and the Cuban dictatorship?

As a joke, it’s said the Cuban revolution is the revolution of calluses. You jump when they step on a callus. It happened to me. And I don’t want to justify myself. A friend says you had to be abnormal to believe in the revolution, and I always respond that yes, I was “abnormal.”

In radio and television and then as president of UNEAC in Guantánamo, my concern was to promote artists and advance the province’s culture. From my village, I won national awards, and that made me proud.

I always had conflicts since secondary school because I never stay silent or almost never do when something is wrong or unjust. In university, being an FEU leader, you wouldn’t want to know how many confrontations I had with the School of Letters’ administration, the UJC, and the Party. So much so that despite having an immaculate academic record, without a fail, without an extraordinary, my evaluation wasn’t the best because I was labeled a “conflictive person.”

Being UNEAC president and not a militant filled me with courage and pride. I believed I was contributing to something great. But they stepped on a very painful callus; they messed with my eldest son. You know well what happened, and I infinitely thank you for your courage in taking the case as a lawyer and assuming his defense, proving the accusation false. I say it publicly. Later, I learned it wasn’t him but me, and there were intentions to link me with human rights movements, which was a horrendous crime at that time. In those days, I was accused of studying Geopolitics and having a Bible in my false ceiling. The truth is I had a Bible, but on my nightstand. And regarding studying Geopolitics, I was shocked; it was the first time I heard the word, and it even sounded vulgar. Almost a joke. When I was president of the Hermanos Saiz Brigade’s Literature section, we made the radio program Arte Tres, and the UJC accused us of making an elite program. Imagine, they criticized us for playing Gonzalo Roig’s music and not the Pasteles Verdes.

It was a difficult time for me, my family, and even my closest friends who supported me unconditionally. Then I discovered another part of the country that was unknown to me until then. And that knowledge brought disappointment, opened my eyes, and made me leave the bubble I had lived in until that moment.

In 1998, Arístides and I left on a cultural contract approved by UNEAC, which certainly helped many artists leave with their families and children at that time, knowing we were leaving permanently. It’s difficult when you talk to foreigners and explain that to leave, we needed authorization, and at that moment, we lost our houses in Cuba.

We published “Fidel Castro, the last dinosaur” in Bogotá with Oveja Negra. It was a book of caricatures with the names the people had given the dictator over the years and some of my texts. But you know, not even outside Cuba is humor allowed, and the Cuban embassy in Colombia waged war on us. We were left without a passport. So we sought protection from UNHCR. My mother died, and I couldn’t travel to the Island for her funeral, as happened to many other Cubans.

Later, we published “El viejo y el mal” with my text and Arístides’ caricatures, made declarations supporting the 75, and in short, when you’re outside, things seem more radical. Of course, our position was already declared, and the break happened, let’s say, for logical reasons.

Someone told me it didn’t suit me to take a frontal position against the dictatorship. I replied it did suit me because I wanted to help those who hadn’t yet opened their eyes not wait for their callus to be stepped on.

In Miami, we collaborated with a newspaper of former Cuban prisoners, where I interviewed many people, and their stories make you wonder if I lived in that same country.

I think many of us have transitioned from disappointment to being called “free thinkers,” until you realize you can’t play in half measures. You have to choose; you’re either for or against. Warmth, turning a blind eye, flirting with the dictatorship, staying silent, decidedly makes you complicit.

You are the partner of Arístides, one of Cuba’s most important cartoonists. What has that relationship meant for you?

Although I’ve partially answered the question, I confess that uniting with Arístides brought me closer to another unknown world, especially the past of Cuba and a Havana that only exists in the memories of those who lived it. Thanks to Arístides, I learned the stories of musicians, politicians, and artists in general. He knew Havana’s showbiz, lived in it, knows much about the capital’s cultural, political, and social life because he’s part of that life he lived from a young age in the 50s as a musician.

He is a creator in every sense of the word. A thousand ideas pass through his head in a second; he’s a great observer of reality, which he knows perfectly and metabolizes incredibly. That makes him an inexhaustible source of knowledge that he transmits and also gives me a contagious strength. I believe we have formed a good duo. Many projects realized over more than thirty years confirm it.

Rebeca and AristidesSince we met, we have talked a lot. It’s fascinating to have someone by your side who not only accompanies you in good and bad times, who is your emotional support, but also an active bibliography with a memory defying the years. Arístides is a chronicler of reality, past, present, and even future. His view on the artistic and social is immensely broad. Life by his side is a constant learning, debating, and refuting. You know how those relationships make one like the alter ego of the other.

Our life together has been productive in doing things; we always have a project. We’ve published several books. In some, the graphic part stands out, and I accompany him with texts, in editing, in curating the work. Other times, the text is strong, and he accompanies it with illustrations. But I confess that in both cases, we both poke our noses in both fields. Each of our books or any event we participate in results from intense and profound exchanges of effort.

I am, according to Arístides, like his “devil,” and of course, it happens in reverse. I read everything I write, and he shows me what he draws. Sometimes we are tough on each other. He usually accepts a critical comment more than I do. Once, not the only time, late at night, he showed me a sketch on canvas. I grimaced and said I would see it in the morning. When I got up and went to see the canvas, he had erased it.

I won’t say everything has been rosy. Sometimes we argue fiercely, criticize each other deeply, without mincing words, as it should be. But time has led us to great empathy and professional complementarity, which I think has saved us as a couple.

Do you think there’s any justification for artists and intellectuals who continue to support the injustices of the dictatorship at this point?

There has never been any justification for supporting the crimes of the dictatorship. I admire those who, from the beginning, understood where the so-called revolution was headed, which has been the start of leftist power in our continent. You have to take a position, one side or the other. You can’t play with God and the devil. And I’m not just talking about Cuba; wherever you live, you have to define yourself because your vote can decide who comes to power. We have seen that whether it’s called socialism, communism, totalitarianism, the left, or globalism, they don’t play games. When they take power, they destroy everything and don’t allow freedom of expression; quite the opposite.

A while ago, information might not reach the Island; it could be distorted or even hidden. Now everything is exposed on social networks as soon as events happen. And in Cuba, you can’t say you don’t know what happens inside and outside. It’s impossible for artists, intellectuals, and anyone on the side of justice to support Castro-communism, which doesn’t even try to hide its radical stance against anything that doesn’t align with them.

How do you evaluate the situation of Cuban writers in exile, considering many of them can’t be read by compatriots on the island? How have you felt the distance from your homeland in your work and life?

You know something? I’ve thought a lot about this topic. And in my concern, I go far beyond the case of writers. In the diaspora, there are many writers, or at least many of us who write and publish, thanks to editorial democracy, both technologically and through free expression, without needing someone’s authorization to publish.

Sometimes I’ve joked that we don’t read each other because we’re busy writing our own books. There are painters, historians, philosophers, journalists, and influencers. The division between exile and insile is getting weaker. Several exile publishers have been publishing writers within the Island, I mean those not part of the officialdom, and social networks contribute greatly to bringing us closer, allowing us to know each other.

It’s difficult to conduct a traditional study of Cuban literature or arts considering generations. The “Castro-communist” time has entirely changed this concept. Literature written in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, carefully kept by their authors, in case they weren’t lost, is published today in exile. You can’t talk about Cuban literature if you only refer to what was published in Cuba during those years. Firstly, for the previous reason, and secondly, because only books published in Cuba under an ideological, not literary decision, are considered. In other cases, salvageable works have been collected, forgotten, and even disappeared from libraries. The same happens with musicians and artists in general who, for leaving the country, were practically eliminated from the official art and literature records.

I’ve thought a lot about the topic because I’m convinced that, thanks to the Cuban diaspora, fertilely scattered across different countries, and especially concentrated in the Cuban community in the United States, even more so in Miami, I believe the Cuban nation has been miraculously preserved. Not just in the arts, but in the culture of guava pastries, croquettes, and ropa vieja; yuca with mojo, ajiaco, and arroz congrí or moros y cristianos.

When theorists and critics decide to create a panorama of Cuban arts and literature of the last sixty-five years, I imagine both insiders and exiles will appear, including the so-called “officialists.” And of course, we will pass to the next world without knowing those records, but future generations will have to do it.

It’s strange, or maybe very normal, and future scholars of the topic will unravel the mysterious ties, visible and hidden, that bind the exiled to their homeland. In my case, and I’ve heard the same from other friends, we consciously enjoy the values of Cuban art and culture more as exile time lengthens. Perhaps because it establishes, against our will, that emotional distance theorists and critics talk about, necessary to release the bonds of nostalgia and longing to recreate our memories.

The recent participation of a delegation of writers residing on the island at the Tampa Book Fair has provoked diverse reactions. What is your position on this?

I wasn’t in Tampa, so I haven’t commented on the fair, but I’m very clear that what we can’t do from exile is flirt with anything that smells official from Cuba.

Now they say culture has nothing to do with politics. Please, tell that to someone else. We know well that behind every step the Cuban dictatorship takes, there is a political intention.

At this point, I have no doubt that the so-called Cuban revolution has been used by the international left for the penetration of socialist ideas in Latin America and the United States.

Since 1959, along with political exiles and people fleeing the Castro-communist regime, many infiltrators came to this country. If not, what has been the well-known Alianza Martiana, based in Miami, which brings together Cubans and people of other nationalities who mostly came young and are now university professors, journalists in major media, and have been and continue to be standard-bearers of communism. They have taken advantage of democracy to sow and cultivate their ideas, hiding behind a manipulated Martian language.

The so-called “cultural exchange” has been nothing more than attempts to undermine the exile’s artistic and cultural foundations, especially in Miami.

Fortunately, many of us are now standard-bearers of the cultural battle, as the Argentine Agustín Laje defines well in his book of the same title. And it is being fought hard in education and the arts.

To cultural and artistic events organized by the Cuban community, of course, we should try to get artists and promoters of the opposition to participate. For some years, “Vista,” an independent art and literature festival, was held in Miami. Sometimes, with much effort to obtain visas, independent Cuban writers were invited. And if they couldn’t come, their books were presented, like when one of yours was presented.

Some think we shouldn’t take a radical position on this matter because then we are doing the same as them on the Island. But it’s not the same. In Cuba, it is the same dictatorship that orders and commands who is published, who performs in a concert, who exhibits their visual work; are we also going to allow those they decide to come to the United States?

Notes:

- Erick Kaupp Gubdeckmeyer (1922-2008), one of the founders of Cuban television. Born in Germany, he emigrated to Cuba and began working in the 1950s as a cameraman at CMQ. Later, he became a director of dramatized programs, including the “Aventuras” segment, which enjoyed high ratings in the 1960s and 1970s and aired at 7:30 p.m. on Channel 6.

- Norma Abad is a director of Cuban radio programs.

- Orieta Cordeiro is a renowned advisor for Cuban radio programs.

- Helio Orovio, a Cuban poet and musicologist, now deceased, was the author of the “Diccionario de la música cubana. Biográfico y técnico” (Dictionary of Cuban Music: Biographical and Technical).

- Mercedes Cros Sandoval, a historian and anthropologist from Guantánamo, resides in the United States. She is a Professor Emeritus at Miami Dade College and an adjunct professor at the University of Miami. She has authored several books on Cuban culture and history.

- Augusto Lemus Martínez, a writer, cultural researcher, and historian from Guantánamo, has lived in the United States for over fifteen years. He has conducted a patient and exhaustive investigation into Guantánamo’s culture, with the initial results appearing in his book “Archivos guantanameros” (Guantanamo Archives).

- Ariel James Figarola, a poet from Santiago de Cuba, now deceased.

- Regarding my entry to UNEAC, it turns out that when I left Cienfuegos in 1985 to move to Guantánamo, the process of forming the provincial committee of that organization in my hometown had already taken place, and I was selected, but I wasn’t informed. So, when the process began in the province of Guantánamo a few years later, I submitted my application, and Havana responded that I had been a UNEAC member since 1985. Curiously, in Guantánamo, Mr. Jorge Núñez Motes, who succeeded Rebeca Ulloa as UNEAC president, never considered me a founding member of the organization and never invited me to the celebrations where the founding members of UNEAC in Guantánamo gathered.

- Enrique Lomba Milán, a philology graduate, researcher, and literary critic, has lived in the United States since the 1990s.

- Ángel Carpio, director of Guantanamo television.

- The story of my poetry book “La fuga del ciervo” (The Flight of the Deer), published in 1995 by Oriente Publishing, as well as the others I published afterward, certainly deserves a chronicle.

- Jorge Núñez Motes, president of UNEAC in Guantánamo from 1994 until this year.

- Personally, I understand Rebeca’s response because friendship is sacred. I don’t remember much about these matters because I was immersed in my work as a lawyer more than in UNEAC, but something that always caught my attention is how Jorge Núñez Motes could become a UNEAC member in the writers’ section without having anything published, considering that Rafael González and Regino Rodríguez Boti, two Guantanamo writers, were denied that possibility. He, who at some point was marginalized in Guantánamo due to his sexual orientation, later became the antithesis of what an intellectual should be, which always seemed unworthy and very unfortunate to me because, without a doubt, he is an intelligent person. Regarding his party membership, it was one of the most scandalous events in Guantánamo, as was his permanence in that position since election results were falsified several times, some conducted without the required number of organization members present for such a vote, something I publicly denounced in one of those elections to Carlos Martí Brenes when he was UNEAC’s national president, at the PCC provincial committee headquarters. That fraud is recorded in one of my agendas.

- For obvious reasons, I know those were very difficult times for Rebeca, and also for me because, as a lawyer, I had to overcome many difficulties just to do my job well. But by then, I was already a “cursed lawyer” and had become accustomed to the hazards of the trade.

- UNHCR, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Rebeca refers to the wave of detentions against peaceful opponents and independent journalists ordered by Fidel Castro coinciding with the start of the United States war against Iraq, known as the “Black Spring of Cuba,” an event that occurred in 2003.

- Agustín Laje is a lucid Argentine writer, political scientist, and lecturer, author of valuable books such as “La batalla cultural” (The Cultural Battle), “El libro negro de la nueva izquierda” (The Black Book of the New Left), and “Generación idiota. Una crítica al adolescentrismo” (Idiot Generation. A Critique of Adolescentism).

- Rebeca refers to my book of short stories “La chica de nombre eslavo” (The Girl with a Slavic Name), whose first edition—and also the following ones—were published by Neo Club Ediciones, Miami, directed by the fraternal Armando Añel.

Roberto Jesús Quiñones Haces